Author: Mike Sokol

I have been a live-sound, recording, and electrical design engineer for 40 years as well as a musician for 55 years and am currently the chief instructor and CTO for the How-To Sound Workshops, presenting seminars about music production in 40 cities a year. During the past ten years I have presented over 600 seminars across North America at churches, recording schools, universities, and professional audio organizations such as the Audio Engineering Society, the Society of Broadcast Engineers and NARAS (Grammy Awards Group). My time is also dedicated to running a blog about electrical shock prevention for RV owners and musicians at www.NoShockZone.org and contributing to www.ProSoundWeb.com.

Sound systems are virtually everywhere. They can be found in various places from the simple pulpit with a single microphone for graduation, to multimedia stages with hundreds of speakers, instruments, and mics for the latest musical sensation. Although professional sound and music gear is safe as designed and built by the manufacturers, once the gear is in the hands of consumers, a lot can happen to cause it to be deadly to consumers.

Very little empirical data exists on how musicians get shocked. In 2011, we ran a survey on ProSoundWeb.com asking how many musicians and sound engineers had been shocked by their instruments or microphones. Out of 3000 respondents, over 70% of the readership had experienced at least one shock on stage, and multiple had even gone to the emergency room after being knocked unconscious and falling off stage. As a musician of over 50 years, and having been shocked multiple times, and rendered unconscious at least once, the findings of the survey set me into action. I decided it was time to build a test bench that could recreate various shock levels at will to educate musicians and technicians about shock hazards on stage.

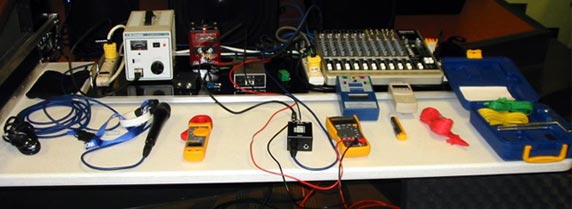

The test bench was basically a self-contained sound system isolated from my larger sound system, since it will be biased with both ground loop currents for hum injection as well as chassis ground voltage for shock demonstrations. The setup included a soldering transformer for demonstrating ground loop currents, a DMM, clamp-on meter, non-contact voltage detector, and ground loop impedance testers. I’ve used B&K Precision instruments in past years and previous careers and have always been impressed with their ease of operation and stable calibration. There were no other companies I contacted who make equivalent AC power supplies with isolated outputs, so I chose B&K Precision’s 1653A and 1655A AC power supplies. I also used B&K Precision’s 309 Digital Earth Resistance Meter for outdoor testing with RVs in varying wet/dry RV park environments and ground testing of buildings.

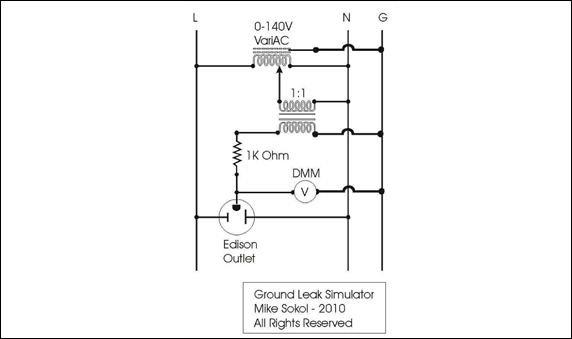

The 1653A and 1655A AC power supplies with isolated transformer secondary windings allowed me to easily bias an entire sound system including microphones, mixing boards, power amplifiers, and speakers with a variable voltage from 0 to 120 volts AC.

This circuit simulated the same effect of a musician plugging his sound system into an ungrounded outlet or an extension cord with the ground pins broken off, where any internal leakage within the electronic gear will bias the chassis towards the high side of the incoming AC power. As part of the live demonstration in these seminars, I start with 40 volts bias on a microphone and note that there's no hum, blue aura, or sparks. 40 volts is often quoted as the minimum dangerous AC voltage for human beings with damp hands and feet. Using a voltage detector, I then show there is a measurable voltage potential on the mic, which would be a shock hazard if the performer was standing on damp concrete or wet grass. Then I use the AC power supplies to bias the system ground to 80 volts AC and show that the voltage can be detected from 2 to 3 inches away with the voltage detector. Finally, I turn up the chassis bias to 120 volts AC. At this level, the voltage can be detected at an astonishing 4 to 6 inches away depending on the surface area of the sound gear being tested.

Over the summer, I discovered that a major lightning strike had struck the iron cross of a church in Texas and “glassified” the building’s ground rod. Located on the roof, this cross was grounded through the building’s electrical system rather than a separate lightning rod. The lightning strike melted the sandy soil around the ground rod, producing a high resistance “popsicle” insulator, which allowed the entire building ground plane to be elevated above the earth potential by 100 or more volts DC when lightning clouds were overhead. They noted that a lighting technician could feel voltage in his fingertips touching a grounded dimmer controller that corresponded to lightning flashes in the sky.

So as a new part of my demonstration, I now show the basics of ground rod testing for buildings that have suffered a lightning strike in the past and recommend using the B&K Precision Model 309 Earth Resistance Meter for testing the ground resistance before putting a building’s sound system back in service. Combined with the 1653A and 1655A variable isolated AC power supplies, these instruments have helped teach shock hazard safety to audio professionals in No Shock Zone and ASSIST (Academy of Sound System Integration, Setup & Troubleshooting) seminars all across the country.

The message for the students was simple: NEVER accept getting shocked on stage. NEVER cut off the ground pin of an extension cord in an attempt to stop hum in a sound system, and NEVER stand in water while touching anything connected to the power line such as a microphone or guitar. We currently have twelve of these ASSIST seminars scheduled in 2012 as well as several No~Shock~Zone clinics aimed directly at musicians.

Mike's Testbench

Mike's Testbench

Ground leak simulator schematic

Ground leak simulator schematic

Detecting voltage 4-6 inches away from microphone

Detecting voltage 4-6 inches away from microphone

Teaching ground rod testing for buildings using the model 309 earth resistance meter

Teaching ground rod testing for buildings using the model 309 earth resistance meter